By Alina Schnake-Mahl, Rebecca Finkel, Jennifer Kolker

Dallas, Texas passed an ordinance in 2019 offering residents paid sick leave, which gives workers paid time off to care for themselves or their loved ones. The city joined Austin and San Antonio, which had also recently passed ordinances offering this benefit. Although it passed well before the pandemic, Dallas’ paid sick leave policy was set to go into effect on April 1, 2020, two weeks after Texas declared a public health disaster. However, one day before it would have been enacted, a federal court judge blocked the ordinance, preempting the city’s efforts and, in effect, the needs of Texas’s urban residents. This unsurprising decision, given the South’s prevalent use of preemption, impacted COVID-19 infection rates, and as our new research suggests, COVID-19 vaccination and vaccination disparities.

In US cities, the nation’s inequities are magnified and more visible. At Drexel University’s Urban Health Collaborative, we use neighborhood-level data and spatial analysis to reveal health disparities among and within cities — often finding dramatic differences between neighborhoods that share boundaries. Identifying these inequities is critical to developing plans to protect the health of vulnerable residents during public health emergencies, and to ultimately address the structural causes of these health disparities.

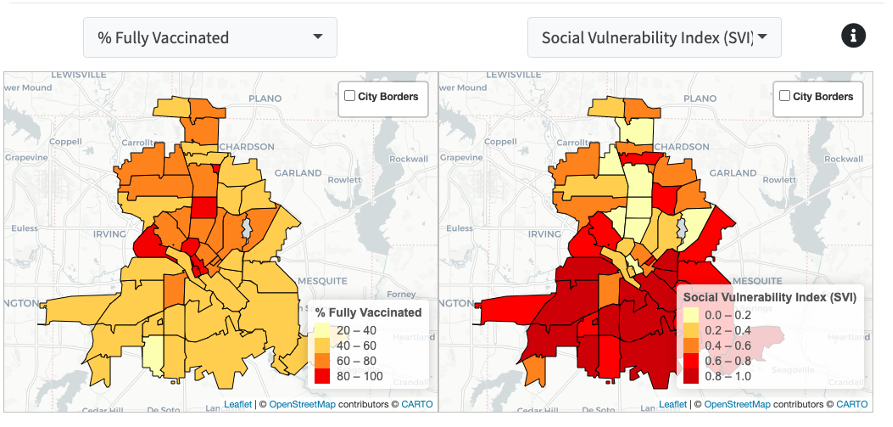

Since the start of the pandemic, our team has found large neighborhood-level disparities in COVID-19 testing, positivity, cases, and mortality. These differences were associated with the neighborhood social vulnerability index (SVI), a measure developed by the CDC to assess a community’s ability to withstand a disaster, such as an outbreak of infectious disease. When COVID-19 vaccines became widely available, we again saw a stark pattern of inequities by neighborhood. In each of the 16 cities we studied, the proportion of people fully vaccinated in each neighborhood (defined as two doses of mRNA-based vaccines or one dose of the Janssen vaccine) was higher in the least socially vulnerable neighborhoods and lower in the most socially vulnerable neighborhoods. The city with the widest difference, at 71%, was Dallas, Texas.

Neighborhood COVID-19 vaccination coverage compared to neighborhood Social Vulnerability Index in Dallas, Texas. Credit: COVID-19 Health Inequities in Cities Dashboard

When Work Determines Risk

Although every city we studied experienced vaccination disparities, some cities had narrower differences. In trying to determine the cause of the differences we observed in vaccination rates, we looked to policies related to a major determinant of health: work.

The US is one of few wealthy countries without a universal paid sick leave program, leaving nearly one in five workers without paid sick leave benefits.2 If an employer doesn’t offer this benefit, it is left to state and local policymakers to pass legislation that determines if and to what degree residents can afford to take paid time off to care for themselves or their families.

This gap in coverage disproportionately affects low-income and essential workers, who have experienced the highest rates of exposure, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19. A recent analysis of COVID-19 mortality by industry showed the highest death rates among workers in accommodation/food service (over half of whom do not have paid sick leave) and in transportation/warehousing, whose recent strike efforts and union demands highlighted paid sick leave as a basic yet unmet safety accommodation.

Compared with those with the ability to work from home or take time off as needed to seek care, these higher-risk workers are also likely to experience higher barriers to vaccination, such as decreased access to health care or unreliable transportation. The Families First Coronavirus Relief Act (FFCRA), passed in March 2020, offered these workers temporary relief, with two weeks of federally mandated emergency sick leave at full pay. FFCRA reduced COVID-19 case rates, which were also lower in states with existing paid sick leave policies, but the federal mandate expired at the end of 2020, before COVID-19 vaccines became widely available, and before we could observe how universal paid sick leave could affect vaccination rates.

Paid Sick Leave Can Raise Vaccination Rates and Reduce Disparities

In order to determine an association between paid leave policies and vaccination coverage, our latest study looked to states and cities with and without paid sick leave policies. Our analysis covered more than 66 million people in 37 cities — nearly 20% of the total US population. When we compared COVID-19 vaccination coverage in cities with and without paid sick leave, we found that vaccination rates of working-age people were higher in cities with paid sick leave policies, even after considering other variables, such as differences in local health systems or political leaning. Importantly, there was no difference in rates among people 65 and older (those more likely to be retired), which supports our finding that the difference in vaccination rates is due to paid sick leave.

Additionally, we found that cities with paid sick leave policies had less variation in vaccination rates by neighborhood. While less socially vulnerable neighborhoods generally had higher vaccination rates, the largest benefits of paid sick leave policies were in neighborhoods with the highest social vulnerability. In future work, we hope to examine not just the presence or absence of paid sick leave policies, but how these policies are implemented: Who is covered, how much time is granted, and how is the availability of these benefits communicated to workers? These factors may be just as significant to worker health outcomes and the reduction of health disparities.

Having, but not Using, the Tools

As we approach our third pandemic winter, COVID-19 vaccination rates among working-age people have stalled, and bivalent booster uptake remains low. While the Biden Administration’s

Fall Playbook for Businesses to Manage COVID-19 and Protect Workers emphasizes vaccination and recommends that business leaders offer paid time off to increase access, it’s not clear that employers are listening. Large companies like Walmart, Amazon, and Walgreens recently reduced COVID-19 related paid time off in alignment with the federal government’s own guidelines that shrank the post-infection isolation period from 10 days to five.

On October 25, the administration announced additional plans to increase use of the bivalent booster, reiterating that “we have the tools” to protect ourselves and our loved ones. These plans include discounts at large chain pharmacies and a partnership with Walgreens, Uber, and DoorDash to offer free delivery of the antiviral Paxlovid to Walgreens customers living in socially vulnerable communities. But how practical are these incentives if those eligible can’t take time off from work to get vaccinated or tested, much less accept deliveries at home? And how durable is a COVID-19 response program that relies on workers who are not guaranteed adequate paid sick leave to protect themselves from COVID-19?

In a way, the Biden Administration is correct: We have the tools, but it is up to policymakers, not individuals to use them. Our study suggests that policies like paid sick leave are key tools to prevent another winter of death and disruption and that universal paid sick leave policies are particularly effective at protecting the most vulnerable communities. But in the absence of federal action, many states have failed to use this tool, and some have gone further by preempting its use by local governments. With COVID-19 vaccination rates lagging in working-age people across the board, it’s well past time for city, state, and federal governments to get to work and enact paid sick leave.