Shane Reader from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health, recently published research in Drug and Alcohol Dependence that reveals patterns in implementation, facilitates future evaluations, and produces a roadmap for the dimension reduction of further policy surveillance datasets related to harm reduction and drug use.

Shane Reader from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health, recently published research in Drug and Alcohol Dependence that reveals patterns in implementation, facilitates future evaluations, and produces a roadmap for the dimension reduction of further policy surveillance datasets related to harm reduction and drug use.

Shane Reader, PhD, MA, is a policy scientist and legal epidemiologist committed to promoting health and opportunity in Texas. He recently completed a Graduate Archer Fellowship in Washington, DC, at the University of Texas Archer Center. Dr. Reader earned his PhD in Healthcare Management and Policy and a certificate in Public Health Law Research and Policy Surveillance at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. He completed his MA in Psychology at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi. Dr. Reader served as the President of the Houston Viral Hepatitis Task Force. His research interests include mental health, infectious disease, emergency preparedness, and health law.

We asked Dr. Reader a few questions about his work.

What did you find in your research?

SR: I think I found some really good ways to take policy surveillance datasets and reduce them to generate new insights and perform more effective evaluations! As a legal epidemiologist, my goal is to evaluate policy in terms of real-world health outcomes. I want to understand which elements of these laws and policies make them successful, and which elements hold them back. But as anybody who’s read a bill or a statute knows, laws are complicated! I’ve been working on 911 Good Samaritan Laws, also called overdose bystander laws, which protect people from certain criminal consequences for substance use if they report a drug overdose. Previously, I did the tedious work of identifying all the ways these laws differ across states, and that information is available in my policy surveillance dataset called the 911 Good Samaritan Law Inventory. The next challenge was to take all this data I have and find a way to crunch it down for modeling, to better make sense of it.

What was the most surprising thing you uncovered as you did your analysis?

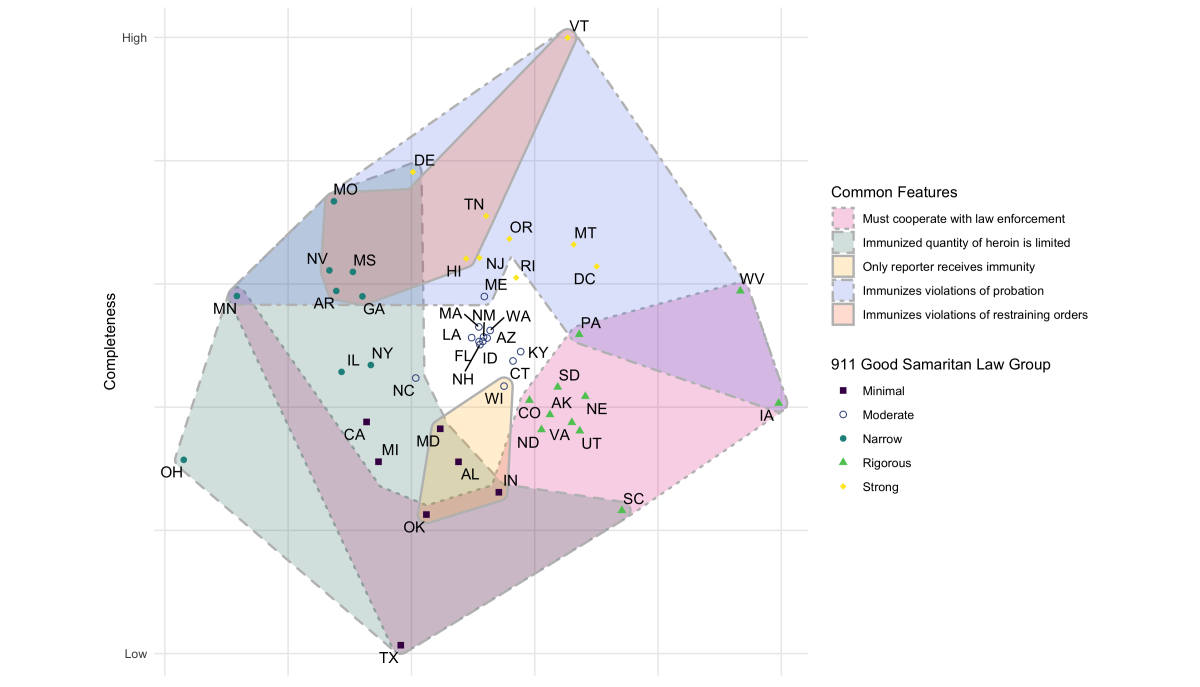

SR: I was really surprised by how different these laws are across states. I think most people agree that a person calling 911 to report an emergency overdose should have some kind of protection, but in my previous research I found a lot of statutory language that limited this protection and some really impactful omissions. That was all qualitative, though! That was me reading and writing about these laws. In this article, however, what I did was use some vintage geometric methods to quantitatively describe the similarity among these laws — or the lack thereof. When we visualize the laws by similarity, putting more similar laws closer together, we can really get an understanding of how variable they are and how we can’t treat them as equivocal.

How did policy surveillance methods support your work?

SR: Policy surveillance is my wheelhouse. My background is psychology where we spend a lot of time thinking about how to take constructs or ideas and operationalize them into something we can measure quantitatively. So, when I first started conducting policy surveillance studies, essentially applying these ideas to statutes and regulation, it came very naturally to me. I think that in the field of legal epidemiology, though, we’re not taking this as far as we should. We still have a lot of studies that treat all laws with the same name as fungible, as all the same. So, in this study what I’m doing is laying a roadmap for other legal epidemiologists and policy surveillance researchers to take all this weird data we collect and better make sense of it using some easy quantitative methods. I think the differences among laws are much more interesting than the similarities.

How can this research help inform policymaking decisions going forward?

SR: In this study, I took all this policy surveillance data on these 911 Good Samaritan Laws, put them all on a map, and organized them into groups. I think advocates and policymakers can both find value in this by finding their state on the map and asking themselves, ‘What will it take to get my state from this part of the map to the part where I’d like it to be?’ Maybe you’re in a state in the Moderate region of the map and you’d like to figure out which small statutory changes can move your state to Strong, or from Rigorous to Moderate. Well, what we’ve done is lay out the distinguishing features which really divide the harm reduction policies in these states.

This figure shows a multidimensional scaling plot of state 911 Good Samaritan Laws. States in closer proximity have 911 Good Samaritan Laws with more features in common. The color of the point indicates the "group" to which the state law belongs, and groups share many features in common. Shaded regions indicate zones on the map in which all state laws express a certain feature. State laws higher on the Completeness axis have more features that protect Good Samaritans.

What should policymakers at the local, state, and federal level do to make an impact on Good Samaritan Laws?

SR: What the qualitative and quantitative literature in this space agree on is that people are witnessing overdoses happen but they’re not calling 911. For these laws to be effective, we need to ensure we’re reaching these communities with a simple message — it’s safe to call 911 to report an overdose, even if you’re using drugs. That’s going to take community outreach, it’s going to require educating people who are using drugs, and we’re going to have to change some of these laws. At the local level, you can tell your district attorney or your mayor that you want a municipal 911 Good Samaritan policy. Your county DA could come out tomorrow with a policy saying they won’t prosecute certain possession crimes under Good Samaritan circumstances. At the state level, I’d be glad to support any advocate who’s telling their legislators how to enhance their 911 Good Samaritan Law. But unfortunately, there’s not a great role for the federal government in this space.

Are there any resources you found helpful that can educate people on Good Samaritan Laws in their state?

SR: There are, and I made one! Anybody who thinks this is interesting should definitely take a look at the 911 Good Samaritan Law Inventory, which is free on Mendeley and was made using CPHLR’s MonQcle software. And I have a review out in the International Journal of Drug Policy that breaks down all the interesting things I found in that dataset. PDAPS, of course, is another great resource.

And if somebody is interested in how to integrate legal epidemiology into their own research domains, my friends at ChangeLab have some great video explainers to help folks get started.

Where should research in this area (including yours!) go from here?

SR: Anybody who reads the study knows that I’m teeing up an evaluation of these laws using a lot of the materials I’ve created here. Keep your eyes out for that. But more importantly, I hope that researchers will take some of the ideas that I lay out in this manuscript and apply them to new domains that I can’t even think of yet.

Legal Program Manager Jonathan Larsen sat down with Dr. Reader and further discussed his research. Watch the Research in Practice video on our YouTube channel or below.